Whispering Trees: Book Review of The Singing Tree

The Newbery Medal once, the Newbery Honor Twice, and the Caldecott Honor all went to author and illustrator Kate Seredy. Seredy was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1899. She grew up with a scattered family heritage, having grandparents from so many different places, and hearing all sorts of opinions and stories. She graduated from college with an art degree and moved to the U.S. soon after in 1922. She illustrated things to provide for herself while learning the English language. Her first book was The Good Master, a book based in Hungary with her as the main character. Four years later, when she wrote the sequel, The Singing Tree, she knew what war was like, having been a nurse in World War I, and was able to write about the hardships that came with it. She continued illustrating and writing books, many of which got notable honors and awards. She always considered herself more of an illustrator than a writer, creating until 1962, thirteen years before her death at age 75 (Young).

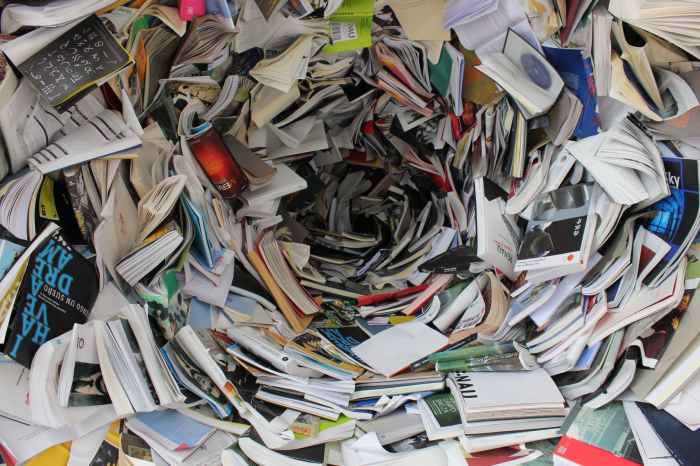

A website titled “A Tribute to Kate Seredy” claimed, “…the best of Seredy’s writing has auditory and visual qualities which draw readers in and carry them along” (Young). This is the first time I have read one of her books and I agree with this statement. In The Singing Tree, at the beginning of each chapter, there is a little traditional Hungarian picture which gives a sense of anticipation and motivation to help the reader continue. The artistry featured pictures at the end of each chapter that are less traditional but they go with the storyline, typically portraying something that happened in the chapter as a little reminder which for me, helped break up the text well.

The target audience for this book is probably early teens to young adults. The book isn’t too thick and loaded with information, yet it isn’t something that you can fly through and not miss anything. I liked that the chapters were easy to manage, taking about 10 to 15 minutes to read about a chapter and a half. The vocabulary and story line are good for teens about 12 up to maybe age 20.

I was surprised by The Singing Tree because I typically don’t prefer books that are historical facts and information. This one was historical fiction and I really enjoyed both the history as well as the style of writing. I knew that Seredy based some characters and settings on her experiences, but it made me wonder how much of the book was fiction and how much she actually experienced. Given her background, I wish Seredy told a little bit more about the war. I understand why she refrained from talking about it, but I felt like if she was going to put a war in her story, there needed to be more context. Every time Jansci’s father shared about his experiences in the war, it was about something important to the story but didn’t give too much context outside of that.

Seredy introduced many characters in The Singing Tree but one of the more important ones is Jansci, a Hungarian boy in his middle teens who values growing up and being a man. He is very thorough and tries to do the best that he can to be like his father, working on the farm and tending all the animals. Village life is all Jansci has known, caring for everything and others recognizing him for being hardworking and helpful. When his father gets called to the war, Jansci knows what to do on the farm because of community, tradition, and how his father has modeled it. Throughout the book he grows up during the worst parts of the war and continues to learn how to do these things without his father, enjoying more responsibilities and learning what he needs to know to be a Hungarian man.

As Jansci is growing up in the village, with him is his cousin, Kate. She is a young teen girl who is very passionate about things, like her chickens. She will not let anyone harm the things that she loves. She struggles to accept all of the restrictions that come with growing up and the things she has to learn. She is in that transition stage between being childish and being a young woman. She still has to learn what the women in the village are called to do which means she has to put certain things aside. For instance, riding horses with Jansci is not how ladies ride horses and the way she dresses now cannot be like men.

I relate with both Kate and Jansci but in different ways. Kate’s determinedness is a lot like me in that she doesn’t give up and is almost always optimistic. Jansci has a sort of sturdiness and quietness to him that I also see a lot in myself. He is an observer of people and that is something that helps us both know a little about what to expect so as not to be caught off guard.

As well as Jansci and Kate, there are other kids in the village who are learning to see life differently. Lily is first seen as a spoiled young girl, having been badly influenced from a fancy school in Paris. She stays with Kate and Jansci while her father is in the war. She slowly gets to know the village and family better, beginning to love and appreciate the animals and farm life. She learns that tradition is supposed to be a cherished ritual, and should be treated with respect, as well as that each animal on the farm is necessary, just as much as each person has value. She has changed from her false “Paris identity” to appreciating the farm as where she belongs.

Seredy shows us how wars change the way people live, and how sometimes, well known truths change in ways that are devastating. Near the beginning of the book, during the war, Jansci is returning home and is required to pick up 6 Russian prisoners. They get stopped by a Hungarian soldier who is looking for one of the men from the village who ran from his duties in the war. He had received a letter that his wife, who had just had a baby, was sick. The soldier doesn’t know that within his load of prisoners Jansci is smuggling the man to their house. The soldier pities the man’s wife saying to Jansci, ”Son, it’s a crazy world when it’s a man’s duty to kill, and a sin to comfort his wife” (Seredy 156). He knows that traditionally it was a man’s job to comfort his wife and a sin to kill, but at the current time, it was the other way around. This was something completely different from their lives before the war. Just as also at the beginning of the book, they count the time by the things that are happening — when the maple turns red, then it’s time to pull the potatoes, etc., but near the end of the book, everybody is counting the time by different things, letters from fathers, nights until a holiday, days since the war started, and more all because of the war’s disruption. These things strengthen one of Seredy’s main themes, change (because of the war) vs tradition (the way of life before the war).

There were a few characters in The Singing Tree who were in denial about the war and they had to accept that there would be some troubles ahead of them. The people have to accept that there will be change and that the traditional ways still remain, they are just altered. A large part of the book is about who the main people are, as well as who the village sees them being. Jansci, Kate and Lily find out what makes them unique and how they can use their special talents to help while the men are away at war. They have to find their identities and roles as young men and women. In a time of war, the farm animals gave the family at home a purpose and a reason to get up in the morning. They were a very subtle way to keep up hope while loved ones were away fighting. The animals provided a source of comfort and healing to families in the community.

No matter what nationality people are, they understand without speaking, the chores that need to be done and the way to do household things. The barrier of language doesn’t matter; the plow will look the same. When people from different areas come in, they help around the farm without asking what to do or how to do it. In the war, both sides are fighting, but they know that this is not the way to settle disagreements. Jansci’s mother realized that the Russian prisoners she took in did not want to fight. They wanted to be at home with their families just like she was. She knew that the country’s leaders were to blame, not the men. She says, ”Why should I mind? They are men, like ours. Maybe… if we are good to them… they’ll write home too, like Sandor, and say that we are kind and maybe some Russian woman will say to her husband or son: ‘Don’t aim your gun too well; they are just simple people like we are’” (Seredy 142-145). It is such a good quote to describe how life during the war affected people on both sides.

The war from Seredy’s Hungarian childhood had a really hard impact on her life and she based this book on her experiences growing up and what she gathered from that. She saw war and suffering and greatly disliked it. She saw how it tore families apart and disrupted daily life. She put a lot of great lessons into her writing that can still apply today – the truth of coming of age and the theme of love without barriers helps the book into a deeper meaning that you have to dig for. She reminds us that we don’t have to speak the same language or fully understand, to help and work together to get the work done. Seredy wanted to teach us there are deep lessons in tradition. As Jansci’s father said, “‘Whispering trees,’ he went on gently as if speaking to them,’they have weathered many storms. Some of them are broken and almost dead, but new shoots are springing up from their roots every year. Those roots grow deep in the soil, deeper than the trees are tall. No one could kill them without destroying the very soil they grow in; what they stand for lives in the hearts of all Hungarians. Nothing could kill that without destroying the country.’” (Seredy 39).

Works Cited

Seredy, Kate.The Singing Tree. New York, Penguin Group,1990.

Young, Linda M. “A Tribute to Kate Seredy, Author and Illustrator.” Flying Dreams, http://home.flyingdreams.org/seredy.htm. Accessed 18 November 2023.

From time to time I will feature student work here on the blog (always with their permission). Maryellen wrote this over a few months in 2023/2024 during our one hour tutoring time each week after reading The Singing Tree. Maryellen is a big reader who is very methodical and observant. I love her keen sense of literary analysis and ability to make textual connections with the world around her as well as other texts. She worked diligently and patiently on this project from drafting to revising to editing!